Sammonmäki Logistics Hub Launches Tuusula’s Focus Area

Developed in cooperation between YIT and Posiva, the grouting method eliminated the major risks related to the schedule of the construction project. The cooperative construction model was highly praised.

For nearly 20 years, a completely unique solution for the permanent disposal of spent nuclear fuel has been under development in the Olkiluoto nuclear power plant area in Eurajoki. Finland is the first and only country to solve the final disposal of nuclear fuel.

“The excavation work is now completed. We still have some building systems to construct. They will be ready in a few months. Then, it’ll be time for tests and trial runs”, says Construction Manager Juha Riihimäki from Posiva.

The testing phase is expected to last until next summer, after which the Government will make a decision on the implementation of ONKALO.

Between 2024 and 2120, Posiva plans to store the spent fuel from the nuclear power plants of Olkiluoto and Loviisa in ONKALO. The encapsulation and repository are planned to be used until about the 2120s.

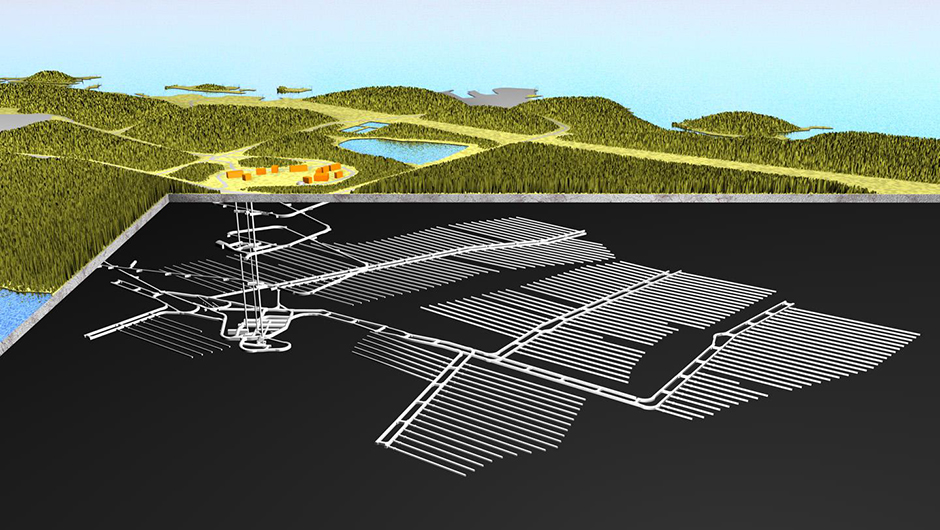

Work falling under the construction permit of the nuclear fuel repository started in 2016 with YIT’s launch of the excavation contract. The work started with expanding the research site excavated previously and proceeded all the way to the disposal tunnels. YIT excavated five disposal tunnels at a depth of approximately 430 metres. The tunnels are 330 metres long.

Four criteria affecting nuclear safety had to be considered during the excavation work: seepage waters, foreign substances, the interference area of the excavation and the drill holes.

“YIT has been in charge of the most challenging phases of the excavation,” says Construction Manager Juha Riihimäki from Posiva.

Construction Manager Juha Riihimäki from Posiva.

About 250,000 cubic metres of bedrock were excavated to make room for the disposal tunnels. All in all, a total of about 550,000 cubic metres of bedrock were excavated from ONKALO.

The completion of ONKALO took nearly 20 years. The last seven years saw the construction of the nuclear power plant.

The excavation of the research site took the first 12 years. Research continued throughout the excavation contract.

“Compared to a usual infrastructure construction project or mining activity, outsiders might think that this is a far cry from any sort of efficiency. However, it must be noted that we’ve done something that’s never been done before, all while facing extremely strict quality and safety requirements,” says Riihimäki.

In addition to the precision of the excavation, the materials used for the construction were specified in detail.

For example, any organic substances, component compounds, plastics, glue, urethane and chemical grouting masses were forbidden due to potential risks to long-term safety.

“Each material or substance brought to the excavated site had to be reported at an accuracy of about one gramme,” says Riihimäki.

“In the event of a hydraulic oil leak from a machine, the leak had to be pinpointed and measured, the oil had to be removed and everything had to be reported in detail.”

One of the leading principles of the excavation contract was to cause as little disruption in the area as possible.

The charging for the blasting work, for example, was limited so that any cracks in the bedrock created in the blasting zone would not reach further than some dozens of centimetres at most.

This work phase called for extra precision and quality control. In theory, the nuclides in the spent fuel could find their way to the living environment by following cracks caused by excavation.

As the cracks fill up with groundwater over time, theoretical scenarios show a possibility of transferring contaminated substances into the environment.

“YIT was involved in the development of appropriate blasting methods that would prevent the bedrock from cracking,” explains Riihimäki.

YIT also used new methods for sealing cracks, also known as grouting.

The company used silica as the grouting material, an unusual choice for rock tunneling. While cement is usually used for grouting, in this case, it was forbidden. Its properties do not meet the quality requirements of nuclear-safe construction.

At the beginning of the contract, the grouting work phase almost delayed the completion of the entire ONKALO project. The grouting and all the necessary inspections related to it threatened to expand into a months-long work phase.

“In terms of schedule, this was the most critical work phase for us. The tunnels are more than 300 metres long. The slow process could have meant that the excavation of the tunnels would have taken longer than estimated,” says Riihimäki.

Finally, about 20 instances of grouting were carried out in the tunnels. YIT was involved in the development of an innovative grouting method, enabling the excavation of the tunnels to be completed in just about over a year. Instead of months, the grouting and the related inspections were completed in days and weeks.

Nuclear-safe construction is all about safety, which is ensured by high-quality construction. A cooperative construction model developed by Posiva and YIT was used for the ONKALO excavation contract. The model is especially fitting for contracts where some of the work phases are difficult to predict.

“From the construction contractor’s point of view, the traditional contract forms were not possible as the work was frequently halted by research. On the other hand, opting for timework as the sole contract solution would have become expensive for us due to all the time spent waiting,” says Riihimäki.

In a cooperative model, the parties to the contract form a joint project organisation and commit to shared objectives and incentives. In the model, the client pays the contractor for any time-based equipment and worker costs but the contractor does not profit from this. The materials, subcontracts and administrative expenses are also invoiced from the client. The contractor’s margin comes from work performances with unit prices. The model encourages both parties to work as efficiently as possible.

The contractor get their bonuses from achieving and exceeding the objectives. On the other hand, enabling the service provider to promote the work as efficiently as possible benefits the client as well.

“We were looking for a happy medium where everyone benefits from the results of high-quality construction. If, on the other hand, the objectives aren’t reached, the parties bear the responsibility.”

The number of occupational accidents reflects the quality of the contract. Only two accidents occurred during the excavation contract, causing only minor scratches. Occupational safety was one of the key objectives of the project. Posiva has high praise for the cooperative construction model.

“Planning a project in cooperation and with shared objectives yields a much better end result. For example, our occupational safety requirements were extremely strict. That was another factor where the cooperative model proved truly helpful,” says Riihimäki.

Rock tunnelling and rock construction services | YIT.fi

All pictures: Posiva.